How to Prevent Retry Storms with Responsible Client-Side Retry Policies

December 22, 2025

On October 19-20th, 2025, AWS experienced a widespread outage that had massive impacts on many applications. The underlying issue, a DynamoDB update that impacted DNS resolution, rippled through the AWS infrastructure and consuming applications. Even after the underlying issue was corrected, infrastructure teams were left working to drain queues, limit traffic, and stabilize services—conditions that set the stage for retry storms and prolonged recovery.

Client applications had very low visibility into all of this; from their perspective, all they could see was that they couldn’t reach the requested resource, so what did they do?

Retry immediately. Repeatedly. This behavior makes sense when interacting with healthy services, because network errors do happen from time to time. But with this outage, many client applications unknowingly made the problem worse by retrying failed requests aggressively — unknowingly amplifying traffic during an already unstable outage.

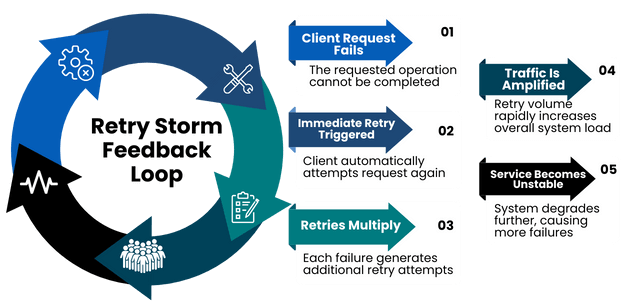

A retry storm occurs when large numbers of client applications retry failed requests simultaneously, spawning additional traffic that overwhelms already unstable systems.

While much of outage prevention rightly focuses on backend systems—load balancers, API gateways, circuit breakers, and queues—client-side retry policies play a critical but often overlooked role in system resiliency. Preventing retry storms requires treating client-side retry behavior as a core part of system resiliency.

In this article, we’ll explore how retry storms form, how client applications unintentionally amplify traffic, and what development teams can do to implement safer, smarter retry behavior.

What Is a Retry Storm and Why It’s Dangerous

Retries make sense when interacting with healthy services—transient network errors happen. But during an outage, retries can multiply dramatically as each failing request spawns additional retries across hundreds or thousands of clients.

This amplification creates a feedback loop:

- Services become unstable

- Clients retry aggressively

- Traffic spikes further

- Recovery slows even more

Because outages often manifest in backend logs and infrastructure metrics, root cause analysis usually focuses on server-side protections– emphasizing circuit breaker management, API gateways, load balancers, and queue policies.

This all makes sense, but clients also have a responsibility to implement sensible retry policies to reduce the initial input into the storm.

How Client-Side Retries Accidentally Amplify Failures

Hidden Retry Layers in Shared Client Libraries

On the client side, a lot of the focus tends to be on the user experience of the application. It makes sense to add silent retries to avoid surfacing unnecessary errors, so it feels natural to write something along the lines of:

await retry(() => axios.post('/search', searchCriteria));

with the intent of retrying three (or a reasonably low number) of times silently before the user notices a failure. In healthy network situations, these individual requests and retries are handled gracefully with little notice. After all, the services are designed to scale to handle large amounts of traffic, and a few retries won’t bother them.

However, when the network becomes unstable and every request turns into multiple retries, traffic is rapidly amplified. How well can your infrastructure handle three times the amount of traffic when it is already unstable?

This baseline amplification is tricky enough, but it is also very common for organizations to wrap their framework client instance in a shared module. This makes it simple to share configuration, authorization, and interceptors in a consistent way across the application.

This configuration will frequently have retry logic configured as well. In this Axios example, the axios-retry library would commonly be used to configure retries. A naive implementation of this could be:

axiosRetry(axios, {

retries: 3,

retryCondition: () => true

});

The result? A single request can turn into nine back-to-back retries, with no delay—hammering an already unstable service and giving no time for recovery.

How Infrastructure Retries Compound Client Retries

In addition to these retries on the framework level, the underlying infrastructure may be retrying connection-level failures like:

- socket resets

- failed TLS handshakes

- DNS resolution errors

Normally this is negligible, but when they are stacked together in unstable network conditions, the latency can become noticeable.

How User Behavior Multiplies Traffic During Outages

While all of these retries are occurring, the user is waiting. If they are as patient with slow software as I tend to be, after about 15 seconds of waiting they will begin trying to fix it themselves. This can include:

- button mashing,

- changing values and resubmitting,

- refreshing the page,

- or other general navigation antics.

This behavior quickly compounds retry traffic across many client instances, pushing even healthy infrastructure past its limits.

Client-side developers can and should take steps to mitigate this.

Client-Side Strategies to Prevent Retry Storms

Use UX Feedback to Reduce User-Generated Retries

The most simple way for developers to reduce the number of user-generated requests is clear communication with users through good UX practices.

These practices really begin with the basics. When users initiate an action, stop them from doing it again. Form validation and submission logic usually include this, but there may be other resource-intensive actions where it isn’t just the button that needs to be disabled, but other related actions as well.

For example, when users are paging through large amounts of data, they may choose to manually type a page number, rapidly navigate to the first or last result, or spam-click the next/prev button. If the results are slow to load, they may then begin utilizing any search or filter features to try to load them faster.

When they are performing these sorts of actions, it may make sense to lock these related UI controls and tell them why they are locked.

Best practices include:

- Disabling buttons after submission

- Locking related UI controls during processing

- Providing visible status feedback

Generally, users are looking for a few types of information depending on how long things are taking. These include:

- Acknowledgement that the system received their input.

Ex: A toast stating “Submitting… hang tight.” - Feedback about what is happening or how long it will take.

Ex: A spinner with a message “We’re processing your order.” - Advice about what to do next.

Ex: A banner: “This is taking longer than expected. Please wait 30 seconds and refresh.”

When it is feasible, adding a cancel button that re-enables the controls can help with the experience as well. This won’t alleviate all frustration, but it can help reduce the amount of spamming.

When to Use Optimistic UI and Cached Data

When it is safe to do so, optimistic UI or cached data can provide a better user experience during slow response times or unstable networks and significantly reduce retry pressure.

If you know that requests will be queued and eventually processed, or that it is not critical for them to be processed immediately, the UI will feel fast if it is updated in real time and then reconciled with the server results later. This will dissuade button spamming from users and make it easier to implement longer wait times between retries.

In use cases where cached data is “good enough,” it can also help reduce user frustration to rely on that instead. For example, if requests to refetch pages are failing, it may make sense to display a banner telling the user that there are connection issues and data may not be current. This provides content and capability while allowing them to make informed decisions.

Centralize and Control Retry Logic

In the retry example from above, the most obvious issue is that retrying was occurring in multiple places in the stack. The easiest way to avoid this is to analyze your stack and determine at what layer retries should be handled, then consistently handle them only in that location (your wrapper, a hook, a helper). If there is a case to add a retry that is not in a centralized location, you should analyze the stack and ensure that it is not calling a function that already retries internally.

It’s easy to say “just centrally implement it,” but before doing so, there are four key configuration options that should be considered.

How to Design Safe Retry Policies

Which API Operations Are Safe to Retry

To retry, an operation should be idempotent – when the operation is performed multiple times, it will yield the same result as if it were executed one time. In most systems:

GET,HEAD, andOPTIONSoperations are inherently safe to retry because they should not cause state changePUTmay be safe to retry if it is setting an exact state, but this depends on the implementation. (The HTTP spec says thatPUTshould be idempotent, but frequently it is not in practice.)POST/DELETEare generally not safe unless the API explicitly guarantees idempotency.

Some operations are not safe to retry because of their business implications. A critical operation that requires explicit authorization from the user, or one that triggers downstream workflows—such as initiating an order, payments, approvals—should likely not retry automatically.

How to Select Retriable Failure Conditions

This is likely dependent on your specific architecture and implementation, but there are some general guidelines:

- Do not retry invalid or unauthorized requests

- Possibly retry if the failure was caused by server health issues, depending on the error and your architecture

- Probably retry network communication failures

Each architecture will have its own nuances, but indiscriminate retries are dangerous.

How to Set a Retry Budget

A retry budget specifies:

- maximum attempts per request

- maximum total retry duration.

For example, it may define a maximum of three retries per request and wait no longer than 15 seconds before returning a meaningful error to the user.

If retries occur for as long as the user has a page open, then they will continue to hammer the struggling services. Without a well-defined backoff strategy with firm limits, retries can continue indefinitely and sustain an outage far longer than necessary.

Exponential Backoff and Jitter Explained

One of the biggest causes of a retry storm is a failure to wait when an operation fails, or multiple requests waiting the same amount of time to retry, which results in synchronized spamming of the service from multiple clients.

This was a major contributing factor leading to the longer recovery time of the October 2025 AWS outage.

As services began to come online, applications were suddenly getting responses to some requests. This increased the overall amount of traffic coming into the system, and rate limits were implemented to give the infrastructure time to scale and stabilize. When requests were rejected then immediately re-queued, the requests from multiple clients synchronized, putting even more pressure on the systems and extending the outage.

The services needed a little bit of breathing room to recover. Adding a fixed amount of waiting time between each retry does not really help, because as the request is rejected and returned to the queue, all clients wait the same amount of time and try again. The requests are still synchronized, just with a slight waiting period between. Rather than having a fixed waiting time, the recommendation is to add Exponential Backoff.

Exponential Backoff is implemented by multiplying the number of attempts by a constant after each attempt, then waiting that amount of time before retrying the request. Exponential backoff increases the wait time between each retry attempt:

- 1st retry waits longer than the 0th

- 2nd retry waits longer than the 1st

- And so on

It spreads out the number of requests by adding variation to when they will be retried and increases the amount of time waiting to give services a bit of breathing room to recover. Even if requests are rejected simultaneously, a request that has been retried twice will wait longer than the request that was retried once.

This helps with the distribution curve but still results in hammering if a large number of initial requests are received at the same time. Exponential backoff alone still risks synchronized retry waves.

What is the best way to stop the retries from synchronizing this way? A little bit of randomness. The addition of a randomizing function to the wait time introduces jitter.

Adding jitter (randomized delay) introduces small timing variations between retries, breaking synchronization and dramatically reducing traffic spikes.

The general exponential backoff behavior is preserved, but since the wait times are not exactly the same, the spikes are avoided.

The concept of Exponential Backoff and Jitter is explained in greater detail on the Amazon Architecture Blog: https://aws.amazon.com/blogs/architecture/exponential-backoff-and-jitter/

A lot of frameworks already include these considerations, or the client application may include libraries that help. The axios-retry example from above supports most of these options out of the box and can be overridden to implement any of them as well as other retry logic.

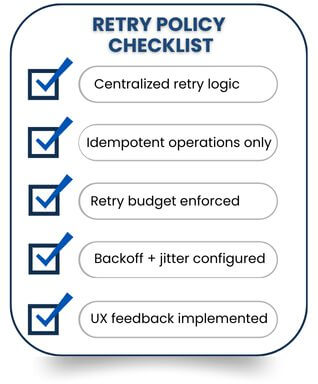

Retry Policy Checklist

Use this checklist to evaluate whether your client-side retry behavior helps systems recover—or unintentionally makes outages worse:

Conclusion: Client Applications Play a Critical Role in Resiliency

Recovering from large-scale outages is never easy, and most of the focus rightfully lands on backend systems, infrastructure teams, and architectural guardrails. But client applications play a bigger role in resiliency than most people realize. A single client retry is no problem, but thousands of them hitting an unstable system can have a devastating impact on recovery.

By implementing:

- Clear UX communication

- Centralized retry policies

- Idempotent operations

- Retry budgets

- Exponential backoff with jitter

development teams can dramatically reduce unnecessary load during failures.

By implementing clear UX communication, centralized retry policies, idempotent operations, retry budgets, and exponential backoff with jitter, development teams can significantly reduce unnecessary load during failures, while also improving system stability and user experience.

More From Rachel Walker

About Keyhole Software

Expert team of software developer consultants solving complex software challenges for U.S. clients.