Design Pattern: Microservice Authentication + Authorization

April 11, 2019

Contributing Authors: Jamie Niswonger & David Pitt

I’ve been in the software development business for a long time and I can’t tell you how many login screens with authentication logic I have implemented. You might say that one of the most prevalent user stories is the need to log in and securely authenticate a user’s access to an application.

Here at Keyhole Software, we have implemented countless login and authentication approaches for applications, along with simple to sophisticated authorization schemes enforcing access control of applications. Of course, you can utilize the single sign-on type of technologies such as OAuth or OpenID, which offload the development of a login UI and the logic for authentication/authorization. However, these standards are not always utilized in enterprise environments. Many enterprises will have a single authentication mechanism that exploits a federated operating system network such as LDAP. A login UI still has to be created and authorization rules still have to be applied to each application.

Over the last few years, we have helped organizations transition away from monolithic-based applications to isolated microservice-based architectures. With Microservices, authentication and authorization logic is now spread across many decoupled distributed processes. It was a bit simpler with monolithic architectures as only a single process is authenticated and contains access control rules defined.

In this blog, we discuss a design pattern for authorization and authentication for use in a distributed microservices environment.

Auth-N and Auth-Z

Before we dive into the specifics, here are a couple of definitions we’ll use throughout this article:

- Auth-N is a term used for authentication of a user’s identity.

- Auth-Z refers to what the user is authorized to do.

The diagram below is a conceptual diagram of a Single-Page Application (SPA) that is driven by a Microservice architecture. This architecture utilizes an “edge” service, that provides “security” and “routing” in front of the microservice infrastructure downstream. The actual Auth-N/Auth-Z processing would be performed by an “auth” service.

When the browser-resident SPA authenticates (i.e Auth-N), it will call through the “edge”, which will delegate to the Auth service. The Auth service simply “authenticates” against the supplied credentials (ie. username/password), and returns an access token to the SPA. You’ll notice this only goes through the edge and has not yet engaged the downstream microservice(s) (or API gateway service).

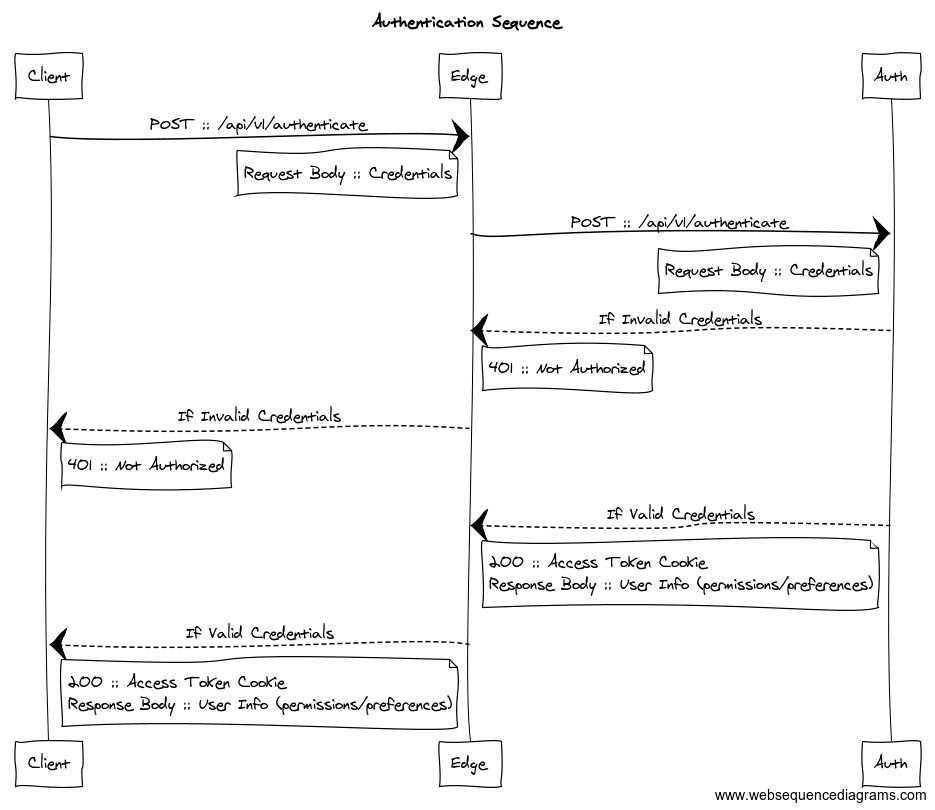

Here’s a detailed sequence diagram of the Auth-N flow:

A valid Access token can be a random unique (opaque) token that has no intrinsic meaning. oAuth or OpenID access will work. You could also implement a homegrown mechanism or existing credential access mechanism (i.e LDAP) to validate the credentials.

Two-factor authentication can also be introduced at this stage. A reasonable timeout request should be applied to this access token and is used by the SPA produced by the authentication service. The access token is used only by the Auth service to validate access and will be replaced with a JWT token (non-opaque) for its journey to the downstream microservice infrastructure. This approach keeps the JWT token away from browser client applications.

Auth-Z

Determining “what” a user can view or what permissions they have is referred to as “Auth-Z”.

Essentially, the Auth-Z mechanism returns information that will be used to determine if the “caller” can perform the request they have made. This information could be some kind of OP code(s) that the Auth-Z mechanism stores and associates with a specific identified user (i.e. user ID), or a role assigned to users. Then as the request travels “downstream”, the “permissions” can be consumed to determine “authorization” at each service.

A consistent standardized way to get these “permissions” to an application is by encoding it into a JWT as claims. This is done at the Auth service since it is aware of a users identity, and can determine their permissions/roles.

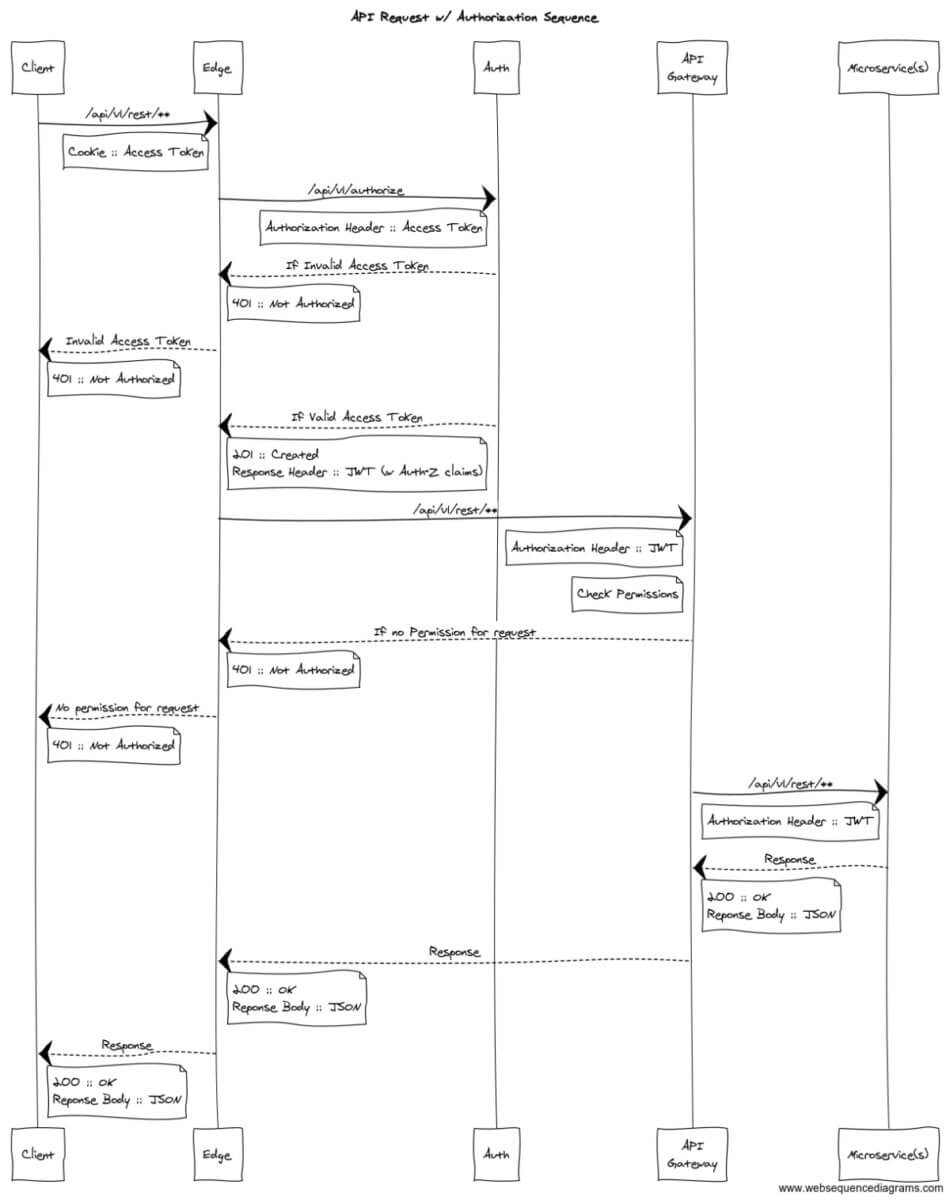

- When an API request is made to the “edge” post authentication, the access token will be supplied and it will ask the Auth-N service for a JWT.

- This Auth service will verify the access token and return a JWT with “permissions” provided as claims.

- The edge will then “route” to the downstream service (API Gateway in this scenario), passing the JWT in an “Authorization” header.

Here’s a sequence diagram for this:

The JWT should be very short-lived; ideally being valid just long enough to ensure it can traverse the entire transaction path (multiple microservices could be involved). In this scenario, the JWT token is never visible to the client browser and will be valid for only one “transaction” initiated by the client.

Since the JWT token has encoded access and identity information, it can move from the API gateway through to the other service implementations, which can then apply and validate this information. Each service (ie. API Gateway and microservices) in the “transaction” path should verify the supplied JWT.

TLS Mutual Authentication of Distributed Services

So far, we’ve discussed how application users of a Microservice style applications are authenticated and authorized. As you can see, there are many “distinct” processes involved in the architecture which means communication between multiple “hosts.”

Traditionally, enterprises will use some kind of symmetric key-based authorization when authenticating one server process talking to another service process. This means a single secret is provided to accessing processes. Then, if this secret is ever compromised, it will be difficult to tell who the nefarious accessor is, forcing the secret to change and having to replace it on all participating entities (i.e. Auth, API Gateway, Services).

An asymmetric-based authentication mechanism involves using a PKI (Public/Private Key Infrastructure) utilizing a Public Key Cryptography to authenticate accesses processes on an individual basis. Each accessing process is granted access with a digital certificate that is produced using a public/private key. This type of asymmetric authentication approach is built into server TLS (transport layer security) mechanisms where digital certificates are used to authenticate access, as well as support encrypted communication on the wire.

The downside to this approach is that every request will have to perform the cryptographic logic to validate the request and public/private keys will have to be managed and deployed to all participating services. That said, we believe the performance hit and management tasks are outweighed by a secure system.

Conclusion

This Microservice Authentication/Authorization pattern can be applied in just about any technology platform. We have successfully done this using Java Spring/Boot frameworks. However, it can be applied successfully with .NET, JavaScript, Go, or any language that allows server-side endpoints that communicate over IP.

If you’d like to see a working example of this pattern, give us a call. We’d be happy to give you access and discuss your needs.

Also, for a deeper dive into Microservice architecture, see this Microservices Whitepaper we’ve put together.

More From David Pitt

About Keyhole Software

Expert team of software developer consultants solving complex software challenges for U.S. clients.

I’m working on a new project at my company and we are building several services that sit behind an API gateway. This is a somewhat new topic to me (I don’t have a lot of experience with Authentication/Authorization) so the diagram is very interesting to me. There are a couple of questions I have about it though… by putting the “Check Permissions” logic within the gateway – doesn’t that make your gateway much larger and couple it to the various micro services you have sitting behind it? I would have expected the gateway to require a JWT, but the actual “Check Permissions” logic to happen within each service, leaving each service as an autonomous process. For ex. in your model, if you add a new api to a service with a new permission requirement, you would have to update both the API Gateway and the service itself, wouldn’t you?

Also, it seems like every request to the server will require a hit on both the authentication data store (to validate user), and on the authorization data store (to check permissions). Can you recommend any patterns for this that lightens the load on those data stores? For example, should the user information be cached to limit the number of database hits, or are there some patterns you could recommend?

Thank you

Jacob,

Thanks for your question, let me give your check permissions questions a try. So our idea of an API gateway is that it is built for a given Application domain. I.e. a given application user interface will have a single purpose API gateway implemented. All the API routes in the API gateway would be for that application, possibly an accompanying mobile or other vendor integration access, but that’s it. It would not be used by other applications. The authenticated JWT token will contain user identity and valid access role information and the API gateway can then apply to the applications API route.

So this allows applying role access at the API gateway communication to the UI appropriately… the UI can also call application API routes to determine what a user can or cannot do. The API gateway will be granted access to the service via TLS/mutual authorization… PKI type cryptography.. The JWT token will also be passed to the services responsible for data access and business logic… services can be reused across applications… and therefore API gateways…

If you have a requirement to apply role access to business logic and data access, then yes, roles defined in the JWT token will have to be applied at the service level. So, these roles should be enterprise-wide since the service are. There is not any reason that Application-specific roles and service enterprise roles can’t make their way into the JWT tokens. So adding a new role-specific to a user of an application does not couple the service to this new role even though the role will be visible to the token.

Regarding your authorization question: When the user logs in successfully, an access token is returned to the UI and is used and validated on each request from the UI to the API gateway. The token is used to create a JWT token for the API gateway and service. We have not had performance issues with this process happening on each request, and yes, you can use caching, etc. to speed performance. Also, a token timeout is traditionally applied, requiring users to re-login after a certain amount of inactivity.

I hope this helps, please reply back with more questions if not.

Thanks,

David

Jacob,

Your intuition is correct on the idea of “caching” at the Auth layer… for example, using a Redis cache to maintain an auto-expiring “token” relationship to the user data is typical. This eliminates the potential load and time spent on the “data store” at each request that you referenced.

As for “Check Permissions” logic…you may very well be able to eliminate authorization at the API Gateway, but there are also more complex scenarios where you may need it there also.

We’ve had some specific scenarios that make this advantageous…for example:

You sell your APIs via a “subscription” model and you have the following APIs:

/api/v1/basicInformation – calls 1 downstream service to provide a response

/api/v1/detailedInformation – calls 2 downstream services to provide a response

If the user only has a “subscription” to /api/v1/basicInformation, then you can “short-circuit” the call to the downstream services (which would typically be reactively (async) called, therefore avoiding two unnecessary calls.

Hope this helps.

jaime